How to determine if LED grow lights are a good investment

|

| University of Arizona Controlled Environment Agriculture Center will host the 14th annual Greenhouse Crop Production & Engineering Design Short Course, March 22–27, 2015. |

|

| A day of hands-on workshops during the Greenhouse Crop Production & Engineering Design Short Course will cover a variety of topics including growing lettuce and herbs in floating systems. |

Visit our corporate website at https://hortamericas.com

Hort Americas just released its newest video designed to help people interested in using supplemental or artificial lighting in hydroponic, vertical farming, urban ag, tissue culture and greenhouse applications.

Whether you are looking to purchase high pressure sodium lamps, need photo-periodic lighting, learn more about LED Grow Lights or simply have any other lighting questions…this video series will help.

Understanding Light Quantity and Its Effect on Commercial Horticulture from C Higgins on Vimeo.

Visit our corporate website at https://hortamericas.com

Tim Blank and our friends at Future Growing, LLC have done it again! Check out this amazing project they did with the city of Chicago and the Ohare Airport.

Completed in September, we wanted to wait till we had a chance to visit it. So check out the video and then the photos from our visit.

|

| Urban Agriculture and Hydroponics |

|

| From Leafy Greens to Herbs to Veggies and Edible Flowers |

|

| Farming of the Future |

Please email us with any additional questions on this project or other hydroponic projects around the world.

Visit our corporate website at https://hortamericas.com

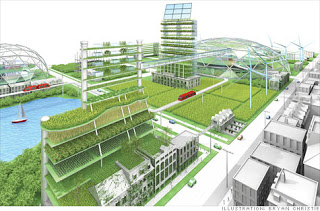

Hort Americas is proud to share this link from CNNMoney.com. The link takes you to an Article on Urban Agriculture (Farming) and the impact it can have on our future. It includes mentions of innovative companies like: Eco Spirit, TerraSphere Systems, Big Box Farms, Gotham Greens and Cityscape Farms and innovators such as Dickson Depommier.

Please read more about the article here:

Urban Farming 2.0: No Soil, No Sun

If there are any questions please email us at infohortamericas@gmail.com.

Visit our corporate website at https://hortamericas.com

The best way to control pest in hydroponics is thru good sanitation practices.

Visit our corporate website at https://hortamericas.com

Hort Americas is continually interested in watching the urban agriculture movement. (Especially as it relates to areas like Detroit, Michigan.)

The below video shows how small farms can bring “life” back to communities.

The next step for these farmers will be to create more opportunities (good paying jobs, growth/education for young people, and community development.)

At this point in time, in order to create a stable environment for all it will be important to create a year round of produce using technology to out smart the Michigan winters and technology to out compete cheap supply from other warmer climates.

It is truly exciting to watch disciplines like controlled environment agriculture, hydroponics, aeroponics, etc. be used as potential tools in an endeavor as important as rebuilding a city, a community and what will become a generation.

Visit our corporate website at https://hortamericas.com

Hort Americas believes that both sides should be heard and looked at when it comes to Hydroponics, Vertical Farming, Urban Agriculture and CEA.

And while we at Hort Americas may believe firmly in new “farming” opportunities, we completely understand the Macro view and their potential limitations.

Please take a minute to read this post from Graham Land at Greenfudge.org and the article by George Monbiot, before you make up your own mind.

In Monday’s Guardian George Monbiot slams the concept of ‘vertical farming’ in a piece, entitled ‘Greens living in ivory towers now want to farm them too’.

His main beef is that a Columbia University parasitologist named Dickson Despommier has been getting a lot of support in the green media for his idea to create skyscraper farms in densely populated urban areas like New York City, which might be a brilliant idea, but it’s a fanciful one as well.

This immediately reminded me of stories about an underground indoor rice farm in Tokyo’s financial district, which turned out to be an expensive publicity experiment.

Monbiot sees vertical farming as a distraction. Water and farmland shortages along with a growing world population bring agriculture and food towards the forefront of environmental issues. Scary stuff in terms of crop failures and resultant starvation for the poor have-nots, but the haves in places like Manhattan are interested in expensive high tech luxury solutions like skyscraper farming?

Despite the impracticality and massive expense the environmental media has been all over it. In a Time magazine article, there is a partial admission of the fault:

“[…] Despommier concedes that it would cost hundreds of millions to build a full-scale skyscraper farm. That’s the main drawback: construction and energy costs would probably make vertically raised food more costly than traditional crops. At least for now.”

Honestly, vertical farming sounds like a cool university project for a designer or architect, but the extent to which it is taken by Despommier seems far from realistic.

I prefer the other kind of urban farming that is happening in Detroit. People move out, abandon houses and land, the remaining folks utilize that land to grow food, which they eat and sell. Brilliant, efficient and not reliant on some expensive high-tech structure in an exorbitantly priced neighborhood. Maybe I’m just completely ignorant, but besides roof gardens, urban gardens or small plots, farming in Manhattan just doesn’t make much sense.

Read about that in this BBC News article:

Urban farming takes root in Detroit

We should be as efficient as we can, but that means behavior suited to the immediate surroundings, not forcing a square peg into a round hole. How about practical solutions like wasting less energy by importing less food? How about growing crops primarily for human consumption rather than wasteful, intensive livestock farming?

Still, if vertical farming happens to work, then fine, knock yourself out.

Visit our corporate website at https://hortamericas.com

Soon to be available at Hort Americas!

Rooftop farming with the Tower Garden is perfect for anyone interested in Hydroponics, Vertical Farming and Urban Agriculture.

Visit our corporate website at https://hortamericas.com

The below information was provided by Philips directly.

Research

“We require reliable products that can be used flexibly for various tests with different starting points. The GreenPower LED module is clear and reliable in its specifications and gives us a great deal of freedom when working with it.”

Dr Wim van IeperenWageningen University and Research Centre

In research it is about discovering, interpreting, and the development of methods and systems for the advancement of plant science. The Philips GreenPower LED module enables you to study the influence of light on the growth and development of plants in conditioned environments. Light level and color spectrum are tunable and test results will not be impacted by heat radiation. Read more about Philips GreenPower LED module.

Tissue culture and storage

“ In our company we saw lots of opportunities for LEDs. By carrying out tests with the GreenPower LED string, we found solutions for both tissue culture and plant storage. As well as saving energy, LEDs help us to improve plant quality, mainly thanks to better heat control.”

Sjoukje Heimovaara, Royal van Zanten

In tissue culture it is about fast, uniform and reproducible production of high quality starting plant material often using low GrowthLight levels. The flexible GreenPower LED string is specially designed for tissue culture, storage and transport. It enables a uniform light distribution across the shelf, ensuring that every crop receives the same level and quality of light. Read more about Philips GreenPower LED string.

Young plants

“Over the past year we have achieved very good results with GreenPower LED modules, using a combination of red and blue light. The next step will be to optimize the yield and quality of our Anthurium production, while taking into account the overall cultivation recipe.” Martin van Noort, Rijnplant Breeding

When producing young plants, high uniformity, strong year-round quality and on-time delivery to the customer are of key importance. With GreenPower LED module it is now possible to tune the light intensity and light color to meet the specific needs at every stage of a crop’s growth. Its specially developed optics and optimized thermal design ensure a uniform light distribution while radiating very little heat toward the plants.

Production/ assimilation

For lighting in greenhouses high GrowthLight levels are required. In the next few years HID lighting continues to be the most efficient solution for growers.

For assimilation in greenhouses too, Philips continues to invest in R&D and field tests to develop horticultural lighting solutions that will create value for growers worldwide. For example, it is currently conducting a major field test – together with a leading tomato grower– with a hybrid of HID and LED lighting. In this way it is seeking to combine the best of both worlds: the GrowthLight power of HID with the flexibility of LEDs.

The knowledge of these tests will help us all to develop meaningful light solutions for greenhouse applications.

We will for sure keep you updated about this project.

For more information on LED lights currently available contact Hort Americas directly.

Visit our corporate website at https://hortamericas.com

www.futuregrowing.comLast week Hort Americas had the pleasure of visiting with a visionary from with-in the commercial Hydroponic Industry.

Tim Blank of Future Growing, LLC (formerly working with Hydroponics for Disney’s Epcot theme park in Orlando) is committed to further developing Vertical Farming and Urban Agriculture. His primary driver is to provide as many people as possible with access to healthy and locally grown food options. If you are seriously interested in learning more about Vertical Farming and Urban Agriculture, we recommend you visit Tim’s website at www.futuregrowing.com. And, if you are interested in purchasing hydroponic towers for your backyard please send Doug Pennington and email at dpennington@hortamericas.com.

Visit our corporate website at https://hortamericas.com

Fortune Magazine post an interesting question?

Can Farming save Detroit?

Visit our corporate website at https://hortamericas.com

Climate Minder is one of the new products Hort Americas is working with. Climate Minder is a wireless environment control greenhouse computer system.

Read about them at Earth Times.

Visit our corporate website at https://hortamericas.com

The U.S. Agriculture Department said Monday the number of households that reported struggling to buy enough food in 2008 jumped 31% over the previous year.According to the USDA’s annual poll, 17 million U.S. households reported some degree of food insecurity in 2008, up from 13 million households in 2007.

“It is time for America to get very serious about food security and hunger,” said Agriculture Secretary Tom Vilsack, who is pressing Congress to expand such programs as food stamps and free school lunches that consume roughly 70% of his department’s budget.Comparable numbers for 2009 aren’t available yet. Officials with organizations involved in feeding the hungry say the survey results square with growing demand at food pantries: the number of people seeking help this summer is up an average of 30% from the summer of 2008, according to a recent survey of food banks by Feeding America, a food-bank network.The 2008 survey results suggest that almost 15% of U.S. households had trouble putting enough food on their tables, up from 11% in 2007; the proportion is the highest detected by the survey since it began in 1995. Put another way, about 49 million people, including about 17 million children, worried last year about getting enough to eat.Maura Daly, vice president of government relations for Feeding America, said 90% of food banks in the recent survey reported that, according to anecdotal evidence, unemployment is the leading factor for the increased demand.

U.S. consumers in 2008 also saw a sudden acceleration in the cost of food. While the food inflation rate has stalled this year, some economists are worried that the move by many recession-weary farmers to cut production might ignite grocery prices again next year.The global recession is helping swell the number of hungry people around the world to the highest levels since the early 1970s.But the way USDA economists measure food worries in the U.S. is far more liberal than their gauge for other nations, where people are labeled food insecure only if they consume fewer than 2,100 calories a day. Few of the U.S. households labeled as food insecure by the USDA have it that tough.Instead, the USDA’s domestic survey tries to quantify the number of households that have difficulty providing enough food at some time during the year. Many of these families are able to avoid hunger by participating in such federal nutrition programs as food stamps, or by having their children participate in a free school-lunch program.Still, the USDA survey indicates that someone in about one-third of food-insecure households experienced some hunger or came very close to it in 2008. In these households with very low food security, food consumption fell and normal eating patterns were disrupted.According to the survey, 6.7 million U.S. households had very low food security in 2008, up 43% from 4.7 million households in 2007.