and quality lettuce plants can be grown hydroponically with organic or

inorganic fertilizers.

81 percent of U.S. families report they purchase organic products at least sometimes.

The study found that the majority of those buying organic foods are purchasing

more items than a year earlier. Those households that are new to buying organic

products represent 41 percent of all families.

category of organic purchases. Ninety-seven percent of organic consumers

indicated they had purchased organic fruits or vegetables in the past six

months. Breads and grains, dairy and packaged foods all scored above 85 percent

among those who buy organic products.

|

| A 2013 study done by the Organic Trade Association showed that 97% of consumers indicated they had purchased organic fruits or vegetables in the past six months. |

results of the study. Organic buyers reported spending more per shopping trip

and shopping more frequently than those who never purchase organic food.

announced its plans to begin offering a new line of organic products called

Simply Balanced. The line is an outgrowth of similar products within its existing

Archer Farms store brand. The Minneapolis-based company plans to boost its

organic food selection by 25 percent by 2017.

inorganic fertilizers

With the increased interest in organic produce by growers,

retailers and consumers, researchers at Kansas State University looked at the

production of hydroponically-grown lettuce using organic fertilizers. Jason

Nelson, who received his Master’s degree this year, said the purpose of the

research was to study overall plant performance with organic and inorganic

fertilizers. Another aspect of the research was to study the effects of

commercial microbial inoculants that are marketed to promote plant growth.

|

| Lettuce plants were grown hydroponically comparing organic and inorganic fertilizer solutions to which were incorporated microbial inoculants. |

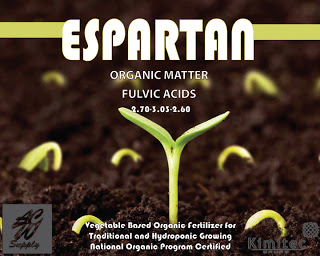

‘Rex’ butterhead lettuce was grown in nutrient film

technique troughs. The nitrogen sources of the complete inorganic fertilizer were

ammonium nitrate and ammonium phosphate. The organic fertilizers consisted of four

Kimitec products for hydroponic production,

including Bombardier (8-0-0), Caos (10.5 percent calcium), Espartan

(2.7-3.0-2.6) and Tundamix NOP (micronutrients), plus KMS (potassium magnesium

sulfate) from a different supplier. The microbial inoculants included

SubCulture-B bacterial root inoculant and SubCulture-M mycorrhizal root

inoculant.

and other complex molecules that break down to ammonium,” Nelson said. “The

ammonium levels could be considered comparable between the two types of

fertilizer systems, although the level was slightly higher with the inorganic

fertilizer. The biggest difference was in the nitrate nitrogen. Starting out,

the inorganic fertilizer contained 75 parts per million nitrate. With the

organic fertilizer there was no nitrate at all. For the other nutrients,

including phosphorus, potassium, calcium and sulfur, using all of Kimitec

products except Katon, which is a potassium source, those were all comparable

with the inorganic fertilizer.”

inoculants was to learn if they had any impact on the plants grown with either

of the fertilizers.

growth using organic fertilizers compared to inorganic fertilizers,” he said.

“These microbial inoculants are advertised as being able to boost plant growth.

One purpose of the study was to determine if the inoculants would boost growth

in an organic hydroponic system so that it would be comparable to plant growth

with inorganic fertilizers.”

growth

One of the things that Nelson noticed in his trials was

that the inorganic-fertilized lettuce plants were harvestable earlier than the

organic-fertilized plants. He said this was particularly evident during the

summer trial when the inorganic lettuce actually bolted.

to the organic, it makes sense that this growth difference occurred,” he said. “There

was more nitrate in the inorganic fertilizer, so there was a better nitrogen

balance from the start and the plants grew and matured a little faster and were

probably about five days earlier to harvest in the summer and fall trials.

nitrate. If a grower added some calcium nitrate to the organic nutrient

solution the plants would catch up to the inorganic plants. I expect it would

only take a small amount of nitrate, 30-50 ppm, for the organic plants to match

the growth rate of the inorganic plants.”

potassium magnesium sulfate were comparable to the inorganic plants in size and

fresh weight. However, the inorganic plants consistently had a higher dry

weight than the organic plants.

said. “If a consumer was buying a fresh head of lettuce they wouldn’t be able

to tell the difference between the organic- and inorganic-fertilized plants.”

the taste of the lettuce. Nelson said that the inorganic-fertilized lettuce is

going take up nitrate nitrogen, which is going to be deposited in the leaves.

inorganic and organic plants,” he said. “I attribute the flavor difference more

to the nitrate level than anything else since the other nutrient levels were very

similar between the inorganic and organic plants. The petiole nitrate level was

much higher in the inorganic plants. The flavor was much heavier. We did an

informal classroom taste-test with students and that was a common response. Many

of them preferred the taste of the organic lettuce over the inorganic lettuce.”

inorganic and organic fertilizers didn’t appear to have any effect on the

growth of the lettuce plants.

stress-free, temperature-controlled environment,” he said. “I really didn’t see

any difference in the studies with the inoculants except in one circumstance.

That was when the solution nutrient levels were incredibly low. The inoculants

actually had some nitrogen bound up in kelp meal as part of their constituents.

I saw some growth differences in that instance.

established and colonize the plant roots. For crops like lettuce which finish

as quickly as four weeks, a mycorrhizal inoculant isn’t going to become active

within such a short production cycle.”

solution pH

Nelson said one of the biggest challenges facing growers

who are trying to grow in an organic hydroponic system is pH management.

adequate amount of nutrients for the plants to grow. But the nutrient solution

required more pH management,” Nelson said. “Managing the pH is the biggest

challenge with organic fertilizers because a grower can follow the recommended

rates so the proper amounts of nutrients are available, but the pH fluctuation

is so much more pronounced than it is with inorganic fertilizer treatments.

solution pH for the inorganic plants was adjusted on average maybe once a week.

For the organic plants, at minimum I was checking the solution pH and electrical

conductivity at least once a day whether I was making any changes or not. Some

days I would check the pH twice. If I checked the pH, adjusted it to what I

wanted, by the next day I would have to add acid to bring the pH back down

because it would increase overnight. Somebody might be able to stretch that to two

to three days. When the plants were young, I was checking every day and

adjusting the organic solution pH every day. That’s what the organic solution seemed

to require.”

Jason Nelson, jsn0331@k-state.edu. Kim Williams, Kansas State University, Department of Horticulture, Forestry and

Recreation Resources; kwilliam@ksu.edu. http://krex.k-state.edu/dspace/bitstream/handle/2097/15574/JasonNelson2013.pdf?sequence=5

Worth, Texas; dkuack@gmail.com.

Visit our corporate website at https://hortamericas.com