Controlled-environment growers have long known the

benefits of grafted plants. Field growers are quickly learning them too.

By David Kuack

Plant grafting of plants has been done for thousands of

years. Preparing and using grafted vegetable plants is common in Asia, Europe

and other regions and is gaining use in North American production systems. North

American greenhouse and high tunnel growers were the first to use grafting most

routinely, but field vegetable growers are showing increased interest in the

benefits grafting has to offer.

Grafting joins the root system of one variety to the

shoot of another variety to create one “hybrid” plant. The plant used for its

roots is called the rootstock. The plant used for its stems and leaves to

produce marketable fruit is the scion.

Matt Kleinhenz, professor and extension vegetable

specialist at Ohio State University-OARDC in Wooster, Ohio, said the number of

vegetable crops that are being grafted is steadily climbing.

“Currently the core crops include tomato, watermelon,

cantaloupe, pepper, cucumber and eggplant,” Kleinhenz said. “These crops are

grafted for various reasons, including their financial value and because their

production can be limited by issues that grafting can address.”

Advantages of

grafted plants

Kleinhenz said there are a number of potential benefits

provided by grafting. These benefits apply to both the person who creates the

grafted plants and the one using them.

“The broadest description of the benefits of grafting may

be that it makes better use of genetics in production,” he said. “Single commercial

fruiting varieties are often hybrids. When developing them, the breeder attempts

to incorporate most or all of the traits that matter into each one. That

process is resource demanding. It takes time and money. It’s technically

challenging and it always involves compromise. Each and every variety is

imperfect in some way. A variety may be better than its predecessors, but it is

still imperfect in some way.”

Kleinhenz said there a number of ways in which hybrid varieties

can be imperfect. They can be less resistant to soil-borne diseases or

deleterious nematodes. They can use water or nutrients inefficiently. They can

be susceptible to various forms of abiotic (nonliving) stresses including cold,

heat or salinity.

“Instead of incorporating all of the desirable traits

into one variety, grafting creates an instant combination of two varieties,” he

said. “The attributes of the two varieties are specifically chosen, but there

is no attempt to blend them into one particular genotype, as in traditional

hybrid development. Instead, grafting provides the best of both varieties by

splicing them together. Through that splicing a new “physical” hybrid is

created for use in that production season only.”

|

Grafting provides the best of two plant varieties by splicing

them together.

Photos courtesy of Matt Kleinhenz, Ohio State University-OARDC |

Kleinhenz said traditional development of a standard

hybrid must overcome barriers to the crossing of the parents, the movement of

traits from one plant to another and the possibility that bad traits tag along.

“In grafting, two varieties must be compatible to be

grafted,” he said. “Grafting allows for the bypassing of difficult and

time-consuming steps that are required to create a superior variety that is

good from top to bottom. For this reason, grafting may increase both the range

of traits available to growers and the speed into which they come onto the

farm.”

Kleinhenz said in those systems that rely heavily on

grafting, scion varieties are bred to produce high quality fruit and rootstock

varieties are bred to power the scion. The scion does not need to resist or

tolerate soil-borne stresses and the rootstock does not have to produce

marketable fruit.

He said grafting combines two excellent varieties in a

matter of seconds. However, an average of two to three weeks may be required to

prepare the seedlings to be grafted and to allow newly grafted plants to heal

before transplanting them.

|

An average of two to three weeks may be required for newly

grafted plants to heal before they are ready to transplant. |

Grafting potential

“Grafted plants are primarily used to limit losses due to

soil-borne diseases and deleterious nematodes,” Kleinhenz said. “Grafted plants

have shown the ability to limit losses caused by organisms that attack the root

system or the lowest shoots just above the soil line. Grafted plants are not

widely used to combat foliar or fruit diseases such as late blight of tomato

that essentially attack the shoot well above the soil line. Foliar disease

management is still primarily the responsibility of the scion.”

Kleinhenz said grafted plants have also performed well under

less than ideal growing conditions.

“Tests completed where soil salinity was high, where soil

moisture was excessive, and when soil temperatures were low have demonstrated

the high potential of grafted plants,” he said. “Grafted plants have also

out-yielded ungrafted ones when conditions were good and they have been able to

use water and fertilizer inputs more efficiently. Researchers and farmers are

testing the performance of grafted plants worldwide under many conditions to

discover where and when using them makes the most sense.”

|

The performance of grafted plants is being tested under many

conditions worldwide to discover where and when using them

makes the most sense. |

Kleinhenz said the preparation and use of grafted plants

is market-driven.

“If users see the benefits, suppliers will offer them,”

he said. “Potential suppliers will be reluctant to prepare large quantities of

grafted plants until they are confident people will buy them.

“I recommend that potential users try them. Local

suppliers and extension personnel can assist in getting started. Growers can

also prepare their own grafted plants with just a little practice. Hands-on and

free web-based training guides are widely available.”

Playing catch up

The use of grafted vegetable plants in soil-based

production systems is much more common outside North America.

“The current cost of grafted plants, unfamiliarity with

the full benefits of using them, not being sure how to use them and their

occasionally inconsistent performance may explain the situation,” Kleinhenz said.

“Early adopters are already fairly convinced. Others are taking a more

wait-and-see approach. Adoption curves for new practices and technologies tend

to be similar. The benefits have to be clear, consistent and compelling to a

core group of growers. Then, word spreads.”

Kleinhenz said even though grafting is not new, until

recently there have been limited resources available in North America for

widespread and intense evaluation.

“The demand for alternative disease management strategies

and vigorous and resource-efficient crops is high,” he said. “New rootstock

varieties are available. More and more people have at least heard of grafting,

grafted plants themselves and/or grown grafted plants. And, the pool of

research-based information to aid growers is expanding.”

For more: Matt

Kleinhenz, Ohio State University-OARDC, Vegetable Production Systems

Laboratory; kleinhenz.1@osu.edu; http://hcs.osu.edu/vpslab.

David Kuack is a freelance technical writer in Fort

Worth, Texas;

dkuack@gmail.com.

Learning how to graft

The “Grafting Guide,”

available from Ohio State University-OARDC, offers a detailed, easy-to-follow

look at the entire process of grafting. It would be of interest to both

inexperienced and experienced grafters.

This comprehensive pictorial guide discusses the splice-and-cleft

graft method for tomato and pepper. It provides information on selecting

rootstocks and how to evaluate the suitability of grafted plants for use in

field and high tunnel production.

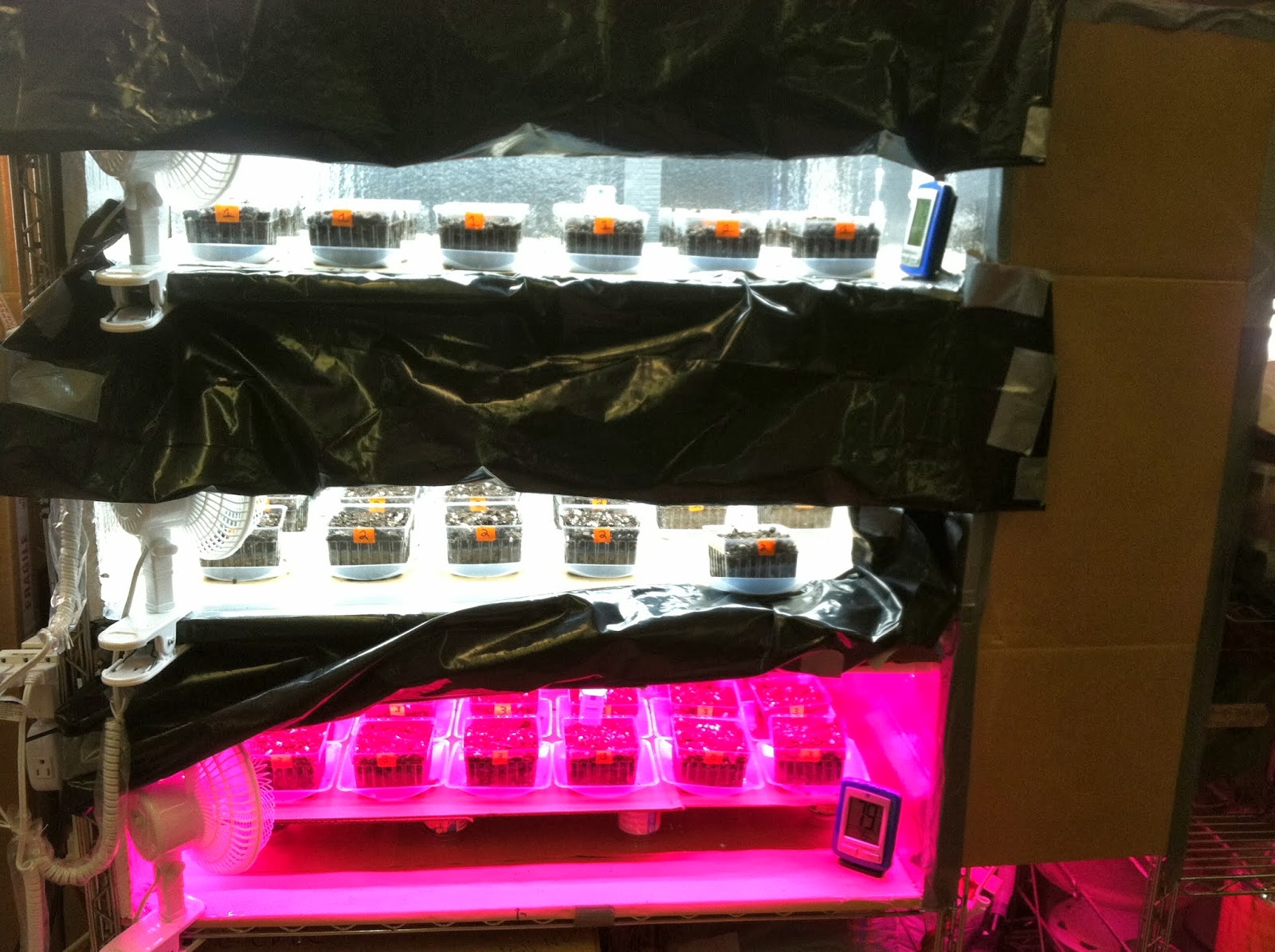

Included in the guide are a tomato rootstock table, seeding

calculator, stem diameter chart, seed treatment fact sheet, healing chamber

design and other reference materials. New additions to the guide will be

prepared as experience and research-based information become available.

Grafting symposium scheduled for Nov. 6

The 2nd annual Vegetable Grafting Symposium will be held Nov. 6, 2013, in San Diego, Calif. The event is being convened by

a USDA Specialty Crop Research Initiative-Supported University-USDA-Industry

Team hosted by the Annual International Research Conference on Methyl Bromide

Alternatives and Emissions Reductions.

The symposium’s objectives include:

1. Summarizing the current status and expected future of

grafting as a technology for enhancing U.S. vegetable production systems

related to profit, resource efficiency and sustainability.

2. Increase the understanding of challenges and

opportunities associated with preparing and using grafted vegetable plants.

3. Strengthen and diversify partnerships required to

widen the application of vegetable grafting as cornerstone technology.

4. Describe the USDA-Industry Team’s goals and approaches.

Visit our corporate website at https://hortamericas.com